Somalia famine aid stolen, UN investigating

click here for story @ http://www.stuff.co.nz/

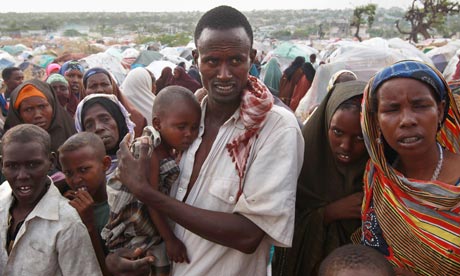

Sacks of grain, peanut butter snacks and other food staples meant for starving Somalis are being stolen and sold in markets, an investigation has found, raising concerns that thieving businessmen are undermining international famine relief efforts in this nearly lawless country.

The UN's World Food Program acknowledged for the first time that it has been investigating food theft in Somalia for two months. The WFP strongly condemned any diversion of "even the smallest amount of food from starving and vulnerable Somalis."

Underscoring the perilous security throughout the food distribution chain, donated food is not even safe once it has been given to the hungry in the makeshift camps popping up around the capital of Mogadishu. Families at the large, government-run Badbado camp, where several aid groups distribute food, said they were often forced to hand back aid after journalists had taken photos of them with it.

"They tell us they will keep it for us and force us to give them our food," said refugee Halima Sheikh Abdi. "We can't refuse to co-operate because if we do, they will force us out of the camp, and then you don't know what to do and eat. It's happened to many people already."

The UN says more than 3.2 million Somalis - nearly half the population - need food aid after a severe drought that has been complicated by Somalia's long-running war. More than 450,000 Somalis live in famine zones controlled by al Qaeda-linked militants, where aid is difficult to deliver. The US says 29,000 Somali children under age five already have died.

International officials have long expected some of the food aid pouring into Somalia to disappear. But the sheer scale of the theft calls into question the aid groups' ability to reach the starving. It also raises concerns about the ability of aid agencies and the Somali government to fight corruption, and whether diverted aid is fueling Somalia's 20-year civil war.

"While helping starving people, you are also feeding the power groups that make a business out of the disaster," said Joakim Gundel, who heads Katuni Consult, a Nairobi-based company often asked to evaluate international aid efforts in Somalia. "You're saving people's lives today so they can die tomorrow."

For the past two weeks, planeloads of aid from the UN, Iran, Turkey, Kuwait and other countries have been roaring into Mogadishu almost daily. Boatloads more are on the way. There is no doubt that much of it is saving lives: the AP saw hungry families lining up for hot meals at feeding centers, and famished children eating free food while crouched among makeshift homes of ragged scraps of plastic.

WFP Somalia country director Stefano Porretti said the agency's system of independent, third-party monitors uncovered allegations of possible food diversion. But he underscored how dangerous the work is: WFP has had 14 employees killed in Somalia since 2008.

"Monitoring food assistance in Somalia is a particularly dangerous process," Porretti said.

In Mogadishu markets, vast piles of food are for sale with stamps on them from the WFP, the US government aid arm USAID, the Japanese government and the Kuwaiti government. The AP found eight sites where thousands of sacks of food aid were being sold in bulk. Other food aid was also for sale in numerous smaller stores. Among the items being sold were Kuwaiti dates and biscuits, corn, grain, and Plumpy'nut - a fortified peanut butter designed for starving children.

An official in Mogadishu with extensive knowledge of the food trade said he believes a massive amount of aid is being stolen - perhaps up to half of recent aid deliveries. The percentage had been lower, he said, but in recent weeks the flood of aid into the capital with little or no controls has created a bonanza for businessmen.

The official, like the businessmen interviewed for this story, spoke on condition of anonymity to avoid reprisals.

The AP could not verify the official's claims. WFP said that it rejected the scale of diversions alleged by the official.

At one of the sites for stolen food aid - the former water agency building at a location called "Kilometer Five" - about a dozen corrugated iron sheds are stacked with sacks of food aid. Outside, women sell food from open 50-kilogram sacks, and traders load the food onto carts or vehicles under the indifferent eyes of local officials.

Stolen food aid is the main reason the US military become involved in the country's 1992 famine, an intervention that ended shortly after the military battle known as Black Hawk Down. There are no indications the military plans to get involved in this year's famine relief efforts.

The WFP emphasized that it has "strong controls ... in place" in Somalia, where it cited risks in delivering food in a "dangerous, lawless, and conflict-ridden environment."

WFP said it was "confident the vast majority of humanitarian food is reaching starving people in Mogadishu," adding that AP reports of "thousands" of bags of stolen food would equal less than 1 percent of one month's distribution for Somalia.

Somali government spokesman Abdirahman Omar Osman said the government does not believe food aid is being stolen on a large scale, but if such reports come to light, the government "will do everything in our power" to bring action in a military court.

The AP investigation also found evidence that WFP is relying on a contractor blamed for diverting large amounts of food aid in a 2010 UN report.

Eight Somali businessmen said they bought food from the contractor, Abdulqadir Mohamed Nur, who is known as Enow. His wife heads Saacid, a powerful Somali aid agency that WFP uses to distribute hot food. The official with extensive knowledge of the food trade said at some Saacid sites, it appeared that less than half the amount of food supplied was being prepared.

Attempts to reach Enow or his wife for comment were not successful.

Businessmen said Enow had several warehouses around the city where he sold food from, including a site behind the Nasa Hablod hotel at a roundabout called "Kilometer Four."

Three businessman described buying food directly from the port and one said he paid directly into Enow's Dahabshiel account, a money transfer system widely used in Somalia. WFP has no foreign staff at the port to check on stock levels or which trucks are picking it up; it relies on Somali staff and an unidentified independent monitor to check on sites.

The men said they would buy in bulk for US$20 (NZ$24) per sack and sell at between US$23 and US$25 - a week's salary for a Somali policeman or soldier.

Until last week, there were daily battles in the capital between Islamic insurgents and government forces supported by African Union peacekeepers. Suicide bombers and snipers prowled the city.

WFP does not serve and prepare the food itself. After the deaths of 14 employees, WFP rarely allows its staff outside the AU's heavily fortified main base at the airport. It relies on a network of Somali aid agencies to distribute its food.

Gundel, the consultant, said aid agencies hadn't learned many lessons from the 1992 famine, when hundreds of thousands died and aid shipments were systematically looted, leading to the U.S. military intervention.

"People need to know the history here," he said. "They have to make sure the right infrastructure is in place before they start giving out aid. If you are bringing food into Somalia it will always be a bone of contention."

In the short term, he said, aid agencies should diversify their distribution networks, conduct frequent random spot checks on partners, and organize in communities where they work - but before an emergency occurs. "It's going to be very, very hard to do now," he added.

At the Badbado camp, Ali Said Nur said he was also a victim of food thefts. He said he twice received two sacks of maize, but each time was forced to give one to the camp leader.

"You don't have a choice. You have to simply give without an argument to be able to stay here," he said.

- AP